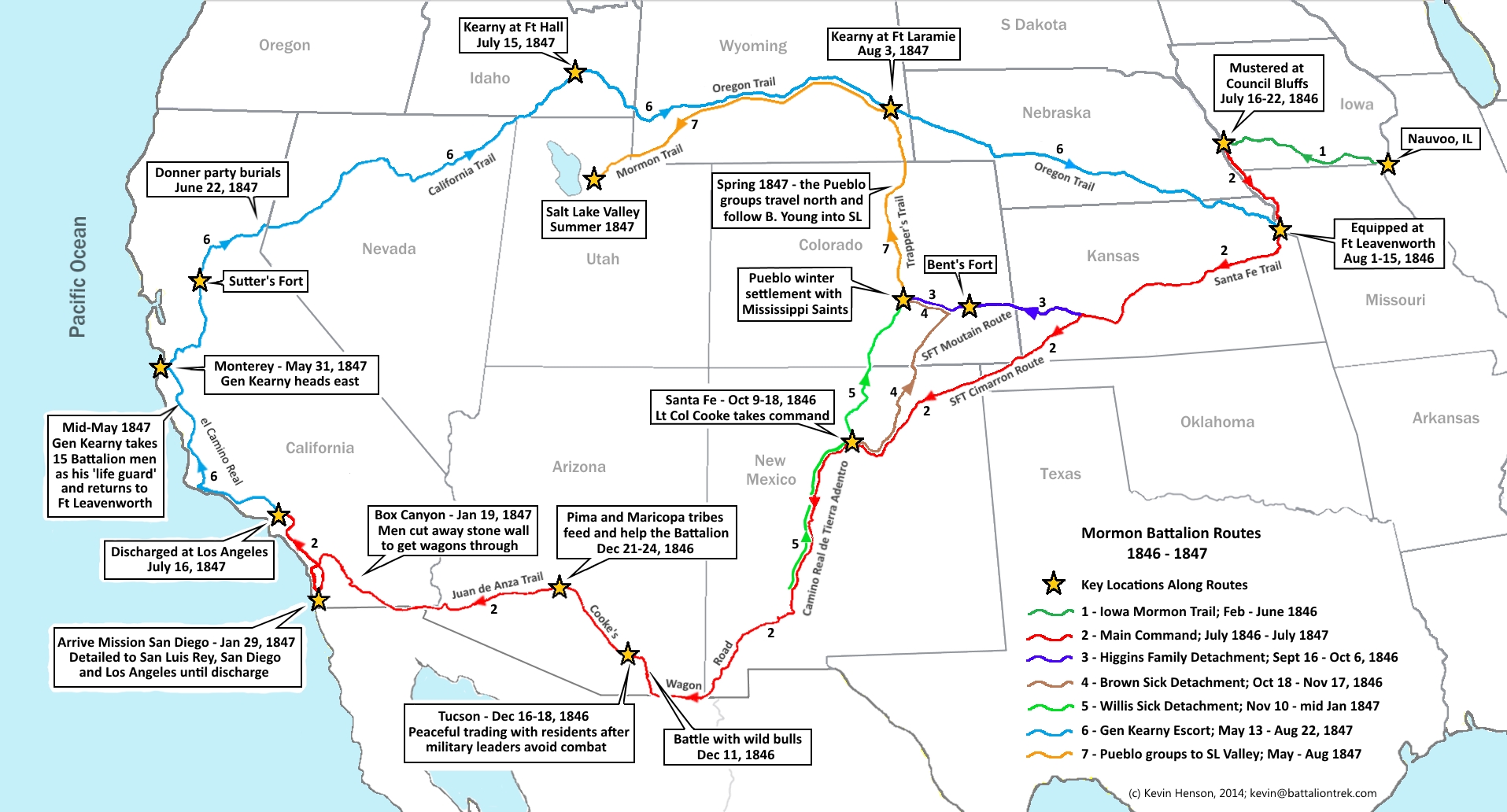

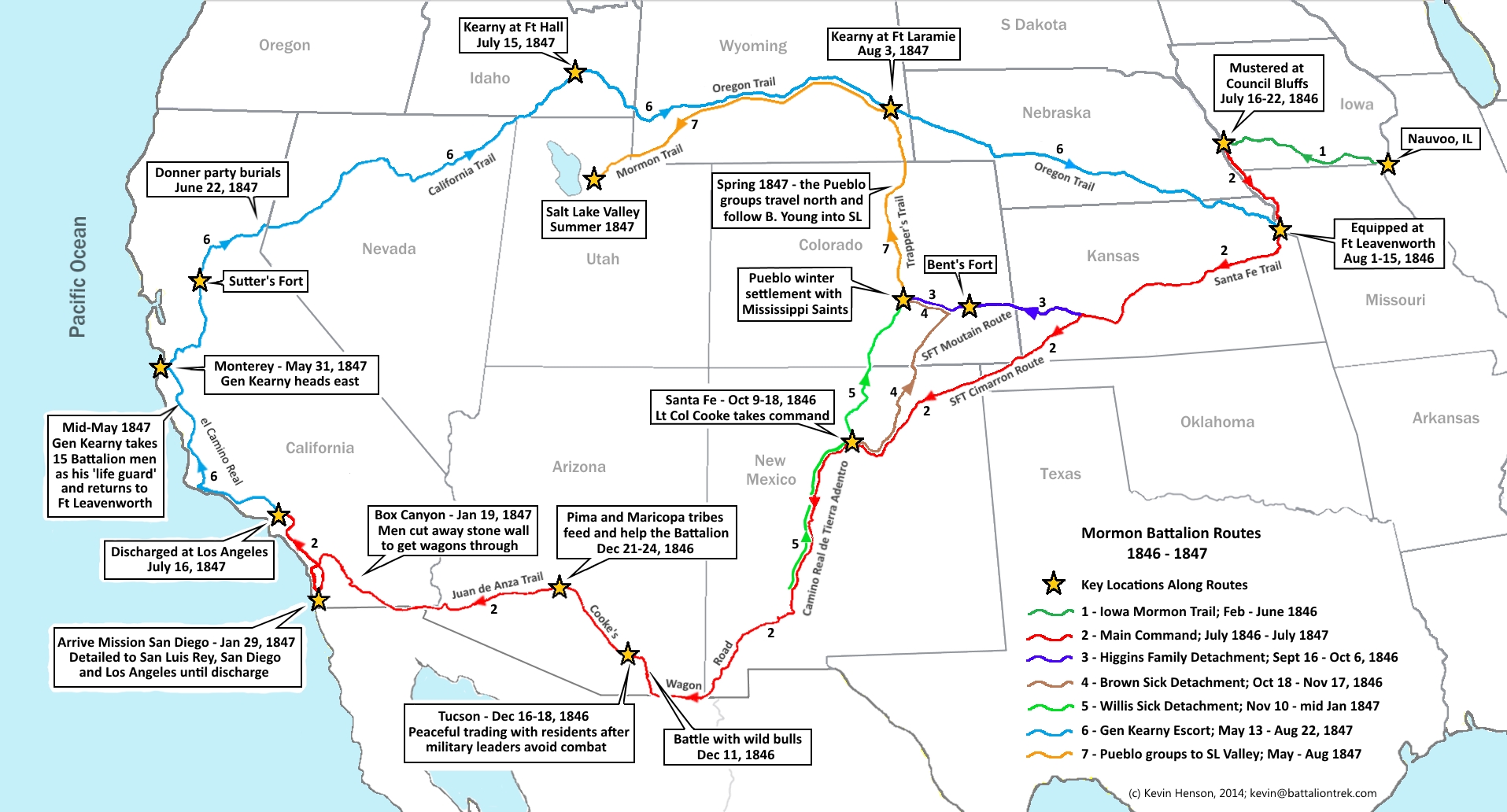

In July 1846, under the authority of U.S. Army Captain James Allen and with the encouragement of Mormon leader Brigham Young, the Mormon Battalion was mustered in at Council Bluffs, Iowa Territory. The battalion was the direct result of Brigham Young's correspondence on 26 January 1846 to Jesse C. Little, presiding elder over the New England and Middle States Mission. Young instructed Little to meet with national leaders in Washington, D.C., and to seek aid for the migrating Latter-day Saints, the majority of whom were then in the Iowa Territory. In response to Young's letter, Little journeyed to Washington, arriving on 21 May 1846, just eight days after Congress had declared war on Mexico. In July 1846, under the authority of U.S. Army Captain James Allen and with the encouragement of Mormon leader Brigham Young, the Mormon Battalion was mustered in at Council Bluffs, Iowa Territory. The battalion was the direct result of Brigham Young's correspondence on 26 January 1846 to Jesse C. Little, presiding elder over the New England and Middle States Mission. Young instructed Little to meet with national leaders in Washington, D.C., and to seek aid for the migrating Latter-day Saints, the majority of whom were then in the Iowa Territory. In response to Young's letter, Little journeyed to Washington, arriving on 21 May 1846, just eight days after Congress had declared war on Mexico.

Little met with President James K. Polk on 5 June 1846 and urged him to aid migrating Mormon pioneers by employing them to fortify and defend the West. The president offered to aid the pioneers by permitting them to raise a battalion of five hundred men, who were to join Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, Commander of the Army of the West, and fight for the United States in the Mexican War. Little accepted this offer.

Colonel Kearny designated Captain James Allen, later promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, to raise five companies of volunteer soldiers from the able-bodied men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five in the Mormon encampments in Iowa. On 26 June 1846 Allen arrived at the encampment of Mt. Pisgah. He was treated with suspicion as many believed that the raising of a battalion was a plot to bring trouble to the migrating Saints.

Allen journeyed from Mt. Pisgah to Council Bluffs, where on 1 July 1846 he allayed Mormon fears by giving permission for the Saints to encamp on United States lands if the Mormons would raise the desired battalion. Brigham Young accepted this, recognizing that the enlistment of the battalion was the first time the government had stretched forth its arm to aid the Mormons.

On 16 July 1846 some 543 men enlisted in the Mormon Battalion. From among these men Brigham Young selected the commissioned officers; they included Jefferson Hunt, Captain of Company A; Jesse D. Hunter, Captain of Company B; James Brown, Captain of Company C; Nelson Higgins, Captain of Company D; and Daniel C. Davis, Captain of Company E. Among the most prominent non-Mormon military officers immediately associated with the battalion march were Lt. Col. James Allen, First Lt. Andrew Jackson Smith, Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke, and Dr. George Sanderson. Also accompanying the battalion were approximately thirty-three women, twenty of whom served as laundresses, and fifty-one children.

Max W. Jamison, Battalion Commander, Mormon Battalion Association confirms that "There is no known basis in fact for the myth that the Mormon Battalion was the

'Iowa 1st Volunteers,' the 'Iowa Mormon Battalion,' or the 'Mormon Battalion of Iowa Volunteers.' It was not listed among the twelve infantry companies in the regiment raised on 26 June 1846 by Iowa Territory. The Mormon Battalion's recruitment on Iowa soil was simply a coincidence of time and place. Rather than being Iowa citizens, its members were unwanted transients emigrating through Iowa and out of the United States on their way to the Mexican province of Alta California. During its entire 1846-47 enlistment, this unique federal volunteer militia unit was simply referred to as the

'Mormon Battalion' on official U.S. Army documents. The first myths that it was an Iowa unit began some 45 years later in 1891, when the US Army Adjutant General's Office printers mistakenly printed Compiled Military Service Record (CMSR) cards referring to the Mormon Battalion an Iowa militia unit. This printing error was officially and consistently struck out by auditors. Sadly, Harvey Reid, an official Iowa State military historian ignored these corrections in his 1910 manuscript Early Military History of Iowa."

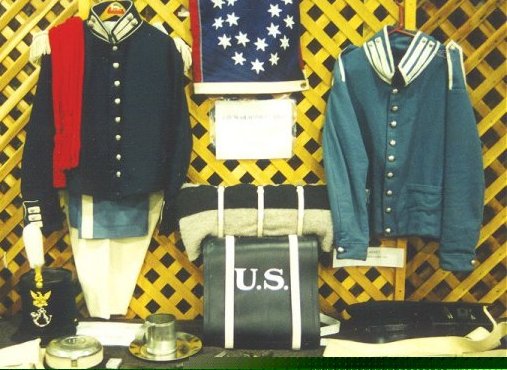

The battalion marched from Council Bluffs on 20 July 1846, arriving on 1 August 1846 at Fort Leavenworth (Kansas), where they were outfitted for their trek to Santa Fe. Battalion members drew their

rations, arms, and accoutrements, as well as a clothing allowance of forty-two dollars. Since a military uniform was not mandatory, many of the soldiers sent their clothing allowances to their families in the Mormon refugee encampments in Iowa. The battalion marched from Council Bluffs on 20 July 1846, arriving on 1 August 1846 at Fort Leavenworth (Kansas), where they were outfitted for their trek to Santa Fe. Battalion members drew their

rations, arms, and accoutrements, as well as a clothing allowance of forty-two dollars. Since a military uniform was not mandatory, many of the soldiers sent their clothing allowances to their families in the Mormon refugee encampments in Iowa.

Each soldier was issued the following: 1 Harpers Ferry smoothbore musket, 1 infantry cartridge box, 1 cartridge box plate, 1 cartridge box belt, 1 bayonet scabbard, 1 bayonet scabbard belt, 1 bayonet scabbard belt plate, 1 waist belt, 1 waist belt plate, 1 musket gun sling, 1 brush and pike set, 1 musket screwdriver, 1 musket wiper, 1 extra flint cap. Each company was also allotted 5 sabers for the officers, 10 musket ball screws, 10 musket spring vices, and 4 Harpers Ferry rifles.

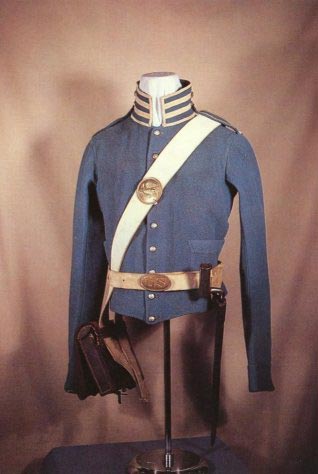

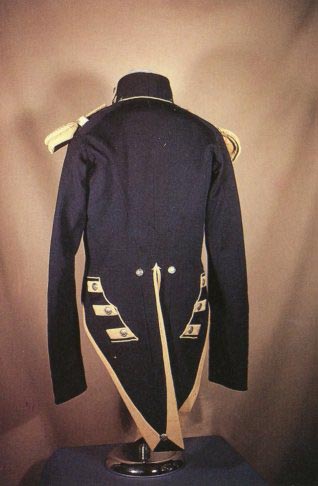

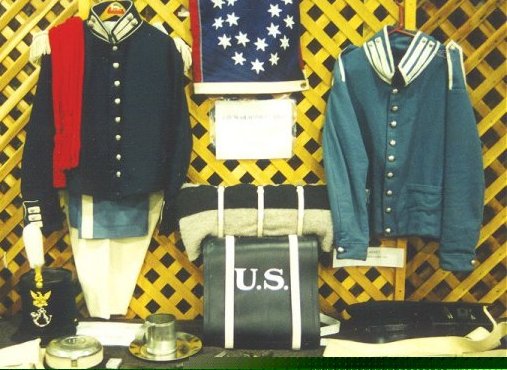

Battalion members took cash in lieu of uniforms, using the money to support their families and their church during a very hard period. Consequently, they did not wear uniforms. The uniform collection shown here is in a private collection. It shows the uniforms that the battalion would have worn had they been issued. The owner of these uniforms often shows them off at gun shows. Click on the image for more info.

The march from Fort Leavenworth was delayed by the sudden illness of Colonel Allen. Capt. Jefferson Hunt was instructed to begin the march to Santa Fe; he soon received word that Colonel Allen was dead. Allen's death caused confusion regarding who should lead the battalion to Santa Fe. Lt. A.J. Smith arrived from Fort Leavenworth claiming the lead, and he was chosen the commanding officer by the vote of battalion officers. The leadership transition proved difficult for many of the enlisted men, as they were not consulted about the decision.

Smith and his accompanying surgeon, a Dr. Sanderson, have been described in journals as the "heaviest burdens" of the battalion. Under Smith's dictatorial leadership and with Sanderson's antiquated prescriptions, the battalion marched to Santa Fe. On this trek the soldiers suffered from excessive heat, lack of sufficient food, improper medical treatment, and forced long-distance marches.

The first division of the Mormon Battalion approached Santa Fe on 9 October 1846. Their approach was heralded by Col. Alexander Doniphan, who ordered a one-hundred-gun salute in their honor. At Santa Fe, Smith was relieved of his command by Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke. Cooke, aware of the rugged trail between Santa Fe and California and also aware that one sick detachment had already been sent from the Arkansas River to Fort Pueblo in Colorado, ordered the remaining women and children to accompany the sick of the battalion to Pueblo for the winter. Three detachments consisting of 273 people eventually were sent to Pueblo for the winter of 1846-47. The first division of the Mormon Battalion approached Santa Fe on 9 October 1846. Their approach was heralded by Col. Alexander Doniphan, who ordered a one-hundred-gun salute in their honor. At Santa Fe, Smith was relieved of his command by Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke. Cooke, aware of the rugged trail between Santa Fe and California and also aware that one sick detachment had already been sent from the Arkansas River to Fort Pueblo in Colorado, ordered the remaining women and children to accompany the sick of the battalion to Pueblo for the winter. Three detachments consisting of 273 people eventually were sent to Pueblo for the winter of 1846-47.

The remaining soldiers, with four wives of officers, left Santa Fe for California on 19 October 1846. They journeyed down the Rio Grande del Norte and eventually crossed the Continental Divide on 28 November 1846. While moving up the San Pedro River in present-day Arizona, their column was attacked by a herd of wild cattle. In the ensuing fight, a number of bulls were killed and two men were wounded. Following the "Battle of the Bulls," the battalion continued their march toward Tucson, where they anticipated a possible battle with the Mexican soldiers garrisoned there. At Tucson, the Mexican defenders temporarily abandoned their positions and no conflict ensued.

On 21 December 1846 the battalion encamped on the Gila River. They crossed the Colorado River into California on 9 and 10 January 1847. By 29 January 1847 they were camped at the Mission of San Diego, about five miles from General Kearny's quarters. That evening Colonel Cooke rode to Kearny's encampment and reported the battalion's condition. On 30 January 1847 Cooke issued orders enumerating the accomplishments of the Mormon Battalion. "History may be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry. Half of it has been through a wilderness where nothing but savages and wild beasts are found, or deserts where, for lack of water, there is no living creature."

During the remainder of their enlistment, some members of the battalion were assigned to garrison duty at either San Diego, San Luis Rey, or Ciudad de los Angeles. Other soldiers were assigned to accompany General Kearny back to Fort Leavenworth. All soldiers, whether en route to the Salt Lake Valley via Pueblo or still in Los Angeles, were mustered out of the United States Army on 16 July 1847. Eighty-one men chose to reenlist and serve an additional eight months of military duty under Captain Daniel C. Davis in Company A of the Mormon Volunteers. The majority of the soldiers migrated to the Salt Lake Valley and were reunited with their pioneering families.

The men of the Mormon Battalion are honored for their willingness to fight for the United States as loyal American citizens. Their march of some 2,000 miles from Council Bluffs to California is one of the longest military marches in history. Their participation in the early development of California by building Fort Moore in Los Angeles, building a courthouse in San Diego, and making bricks and building houses in southern California contributed to the growth of the West.

Following their discharge, many men helped build flour mills and sawmills in northern California. Some of them were among the first to discover gold at

Sutter's Mill. Men from Captain Davis's Company A were responsible for opening the first wagon road over the southern route from California to Utah in 1848.

Historic sites associated with the battalion include the Mormon Battalion Memorial Visitor's Center in San Diego, California; Fort Moore Pioneer Memorial in Los Angeles, California; and the Mormon Battalion Monument in Memory Grove, Salt Lake City, Utah. Monuments relating to the battalion are also located in New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado, and trail markers have been placed on segments of the battalion route.

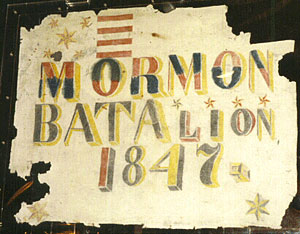

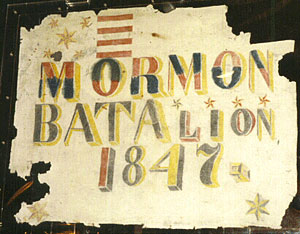

The image to the right is of a Battalion flag owned by, and is in the possession of, a descendant of a battalion soldier. I don't have information on who the descendant (or the ancestor) is, but I believe the owner is in Salt Lake City, Utah. I assume that this flag was carried on the march. A Battalion member named Daniel Tyler wrote the book A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War (available from www.mormonbattalion.com) in which he described a reunion of Battalion members held in Salt Lake. The reunion was also attended by Brigham Young and other LDS leaders. Mentioned in the reunion chapter is a Battalion flag with an image of Abraham's ram in a thicket. That flag symbolized the Battalion as a sacrifice which saved the church just as Abraham's ram was a sacrifice which saved Isaac's life and his posterity (Genesis 22:1-12). The flag shown

here clearly is not the reunion flag. I've never seen a picture of the reunion flag and have never seen any reference to it other than in Taylor's book. I'd sure like to know if this flag still exists. I assume that the reunion flag was created some time after the Battalion was discharged. The image to the right is of a Battalion flag owned by, and is in the possession of, a descendant of a battalion soldier. I don't have information on who the descendant (or the ancestor) is, but I believe the owner is in Salt Lake City, Utah. I assume that this flag was carried on the march. A Battalion member named Daniel Tyler wrote the book A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War (available from www.mormonbattalion.com) in which he described a reunion of Battalion members held in Salt Lake. The reunion was also attended by Brigham Young and other LDS leaders. Mentioned in the reunion chapter is a Battalion flag with an image of Abraham's ram in a thicket. That flag symbolized the Battalion as a sacrifice which saved the church just as Abraham's ram was a sacrifice which saved Isaac's life and his posterity (Genesis 22:1-12). The flag shown

here clearly is not the reunion flag. I've never seen a picture of the reunion flag and have never seen any reference to it other than in Taylor's book. I'd sure like to know if this flag still exists. I assume that the reunion flag was created some time after the Battalion was discharged.

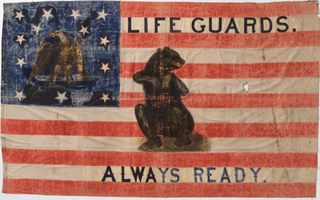

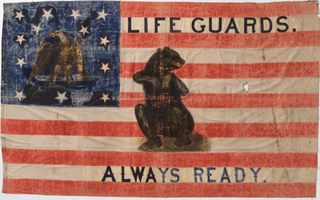

The

image to the right is of a nine-foot-long Battalion flag reportedly was used by

the Nauvoo Legion in Nauvoo, Illinois and later presented by Brigham young to

the Mormon Battalion for their march to fight in the war with Mexico. It is

believed to be the flag raised by the Mormon Battalion at

Camp Moore, Los Angeles, California on July 4, 1847. When Battalion members

rejoined the body of the Saints (by then in Salt Lake City), the flag was

presented to Brigham Young. See "Secrets

of the patriarch's bear flag" for more information. See "Historical

Flags of Out Ancestors" for other flags flown over Utah including Mormon

Battalion flags. The

image to the right is of a nine-foot-long Battalion flag reportedly was used by

the Nauvoo Legion in Nauvoo, Illinois and later presented by Brigham young to

the Mormon Battalion for their march to fight in the war with Mexico. It is

believed to be the flag raised by the Mormon Battalion at

Camp Moore, Los Angeles, California on July 4, 1847. When Battalion members

rejoined the body of the Saints (by then in Salt Lake City), the flag was

presented to Brigham Young. See "Secrets

of the patriarch's bear flag" for more information. See "Historical

Flags of Out Ancestors" for other flags flown over Utah including Mormon

Battalion flags.

See also: Mormon Settlement In Arizona: A Record of Peaceful Conquest of the Desert by James H. McClintock, Phoenix, Arizona, Manufacturing Stationers Inc, 1921 (Chapter 1 covers the Mormon Battalion)

|

The

image to the right is of a nine-foot-long Battalion flag reportedly was used by

the Nauvoo Legion in Nauvoo, Illinois and later presented by Brigham young to

the Mormon Battalion for their march to fight in the war with Mexico. It is

believed to be the flag raised by the Mormon Battalion at

The

image to the right is of a nine-foot-long Battalion flag reportedly was used by

the Nauvoo Legion in Nauvoo, Illinois and later presented by Brigham young to

the Mormon Battalion for their march to fight in the war with Mexico. It is

believed to be the flag raised by the Mormon Battalion at